The Third Component of Integral Mission

I’ve been feeling bad about my first blog post on the EA, Oasis and sexuality. Not because I regret expressing those views or because I’ve changed my mind, but simply because in a tiny way it has fed into the evangelical obsession with sexuality that is more than a little misplaced. So I’m sorry.

In a context where the majority of the world still don’t know Jesus Christ and a child dies of hunger every 10 seconds (3 million a year), it strikes me as grossly insensitive to put that much effort into discussing where evangelicals draw their boundaries – frankly, does it really matter? What makes the 3 million children dying each year from malnutrition (or related causes) particularly poignant is that the world has enough food. It was Amartya Sen (recently voted Prospect Magazine’s top thinker of 2014) who was one of the first to point out that the problem isn’t a global lack of food, the problem is a lack of adequate distribution. In Development as Freedom, he wrote,

“No famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy — be it economically rich…or relatively poor.” “Famines are easy to prevent if there is a serious effort to do so, and a democratic government, facing elections and criticisms from opposition parties and independent newspapers, cannot help but make such an effort.”

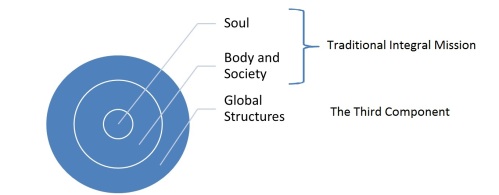

This was a point that I don’t think the recent IF campaign made enough about. But the reason I raise this issue is that it illustrates an issue that I still think evangelicals haven’t quite grasped properly. In the late 19th and early 20th Century, we forgot our previous historical embrace of a holistic gospel and for about 50 years or so embraced a bizarre and highly unbiblical emphasis on soul-winning alone. In the late 1960s and 70s, we recovered the far more biblical emphasis on the so-called social gospel and Holistic Mission was rediscovered.So in 1968, The Evangelical Alliance Relief Fund (TEARFUND) was born; in 1974 the Lausanne Covenant, which explicitly affirmed both evangelism and social responsibility, was written; and since then Integral Mission has become the only word on the street that matters. I have written about this elsewhere.

Under that banner, we have rightly tried to build communities, empower women, teach girls (and boys), feed the hungry and heal the sick, all of which is incredibly important and literally life-saving. But at the same time, there is something more: we also need to tackle what a number of theologians have called ‘The Global Structures of Sin’. In his brilliant book, Bad Samaritans, which to my chagrin I’ve only recently encountered , Paul Vallely lists a number of these including:

- The colonial and post-colonial legacy which as well as asset stripping, created internal elites, fostered social divisions, and led to the ongoing problem of corrupt national governments

- Imposition of free trade, including penalties for protectionism

- Loans and structural adjustment imposed by the IMF and World Bank

- Injustices in the global trading system

- Behaviour of transnational corporations, especially in regard to tax avoidance

He wrote about these in 1990 but the truth is that these global systems of injustice are probably even more significant today than they were 24 years ago. A number of Christian aid agencies are and have been speaking out on them (most notably Christian Aid but see also the Exposed campaign). However, I’m not quite sure that the message has got through to the pews where, it seems to me at least, the focus remains the child I sponsor, the school I helped build, the latrine I have twinned with – rather than the corporate behaviour of AIG, Rio Tinto or Cargill.

If in the past we have focussed only on the soul (leaving aside what we mean by that term for a moment), we have in the last half century re-discovered the body and society (shelter, food, clothing, safe working conditions, fair pay etc) but it strikes me we need to further expand our vision of what Integral Mission means and also now pay attention (if not all of our attention) on the global system in which these souls and bodies live (and given climate change arguably future generations as well). What that means in practice is not always straightforward, but supporting the tax justice and trade justice work of Christian Aid or Tearfund’s Secret’s Out campaign could be a start. Such initiatives aren’t ‘sexy’ (which given the phenomenon of poverty porn is arguably the right word) but I’m at least convinced that this kind of work is where our energies should lie.

Often, we’ve interpreted the parable of the good Samaritan as if it’s about helping our neighbour in need. The problem with that interpretation is that if that was all Jesus was trying to say then he would have made the Samaritan the man in need rather than the one who helped. The parable was a response to a question about the law from one who was seeking to keep his world separated into those whom he was required to love and those he could ignore. By telling the parable, Jesus wasn’t encouraging the expert in the law to love his neighbour – he already knew that – he was encouraging him to expand his category of who he called ‘neighbour’. He was, in other words, addressing a structural issue at the heart of Palestinian society. Structures of sin are systems, assumptions, behaviours and beliefs that facilitate or perpetuate sin in society. For the Jewish religious leaders, the belief that the Samaritans were their enemies who not only could, but should, be hated, represented precisely such a structure.

There is a pressing need for us also to address such structures of sin in our own global society. Melba Maggay, a theologian and activist from the Philippines, has captured well the change in emphasis that is required:

There are many small and promising initiatives, particularly the fairly large microfinance industry. But these mostly manage to keep the heads of the poor above water. While micro-lending and others such acts of mercy are always good in themselves, these cannot substitute for hard social analysis and confronting the power structures that hold so many hostage to poverty. Evangelicals are unfortunately stuck in merely providing discrete services to the poor, without addressing the larger context of why people are poor. There is a reluctance to engage in advocacy, to create a public voice and insert the cause of the poor into political space.

This is the move from charity to justice that Vallely first spoke about 24 years ago. It strikes me that it’s a call that has not yet been heard sufficiently.